Editorial

I've been watching two genres compete for cultural attention, and the winner isn't the one you'd expect.

Climate fiction should be dominating. We're living through the crisis it depicts. The stakes are real, immediate, and measurable. Yet when I look at what's actually moving audiences, what's creating shared cultural moments, what's making people show up—it's space opera.

Dune: Part Two opened to $178.5 million globally in March 2024, nearly doubling its predecessor's debut, and went on to gross a staggering $714.8 million in total. Warner Bros. president Jeff Goldstein called it a moment that "really permeated the culture." That's not franchise momentum. That's something else.

To illustrate this paradox, look no further than Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)—arguably the most celebrated climate fiction film of the last decade. Directed by George Miller, the film is set in a world ravaged by ecological collapse and water scarcity, making it a quintessential example of Hollywood climate fiction. Mad Max: Fury Road grossed $380.4 million worldwide—an impressive figure, but still less than many space opera blockbusters.

The Architecture of Impact

Climate fiction operates under a structural handicap it can't escape.

Research from Duke University Press found that climate fiction provokes environmental anxieties but produces minimal behavioural change. Readers adopt solitary consumption-based measures—recycling more, buying different products—but rarely pursue collective action or systemic engagement.

The genre raises awareness without creating momentum. It makes you feel the problem without showing you the system.

Colby College Professor Matthew Schneider-Mayerson studied climate fiction's effects and concluded:

"We sometimes fetishize raising awareness. Awareness is valuable, but we're aware of lots of things that never affect the way that we act."

Space opera doesn't have this problem because it isn't trying to solve the same equation.

What Space Opera Actually Does

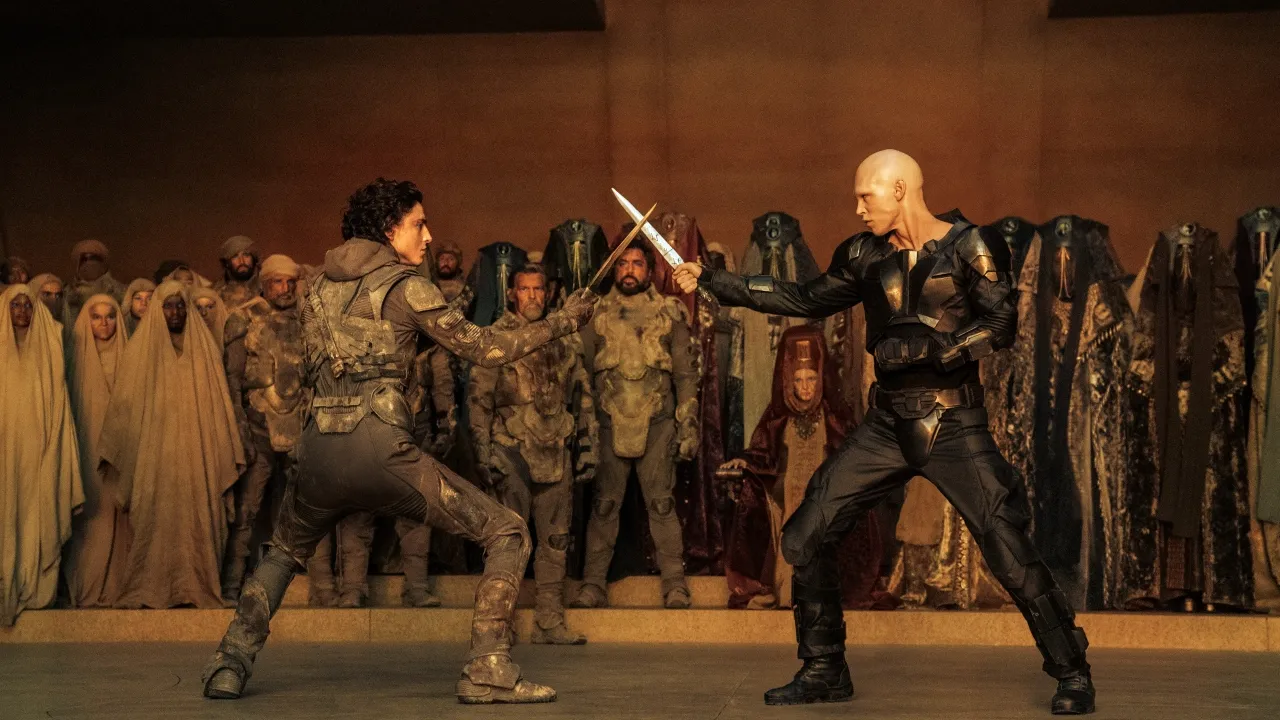

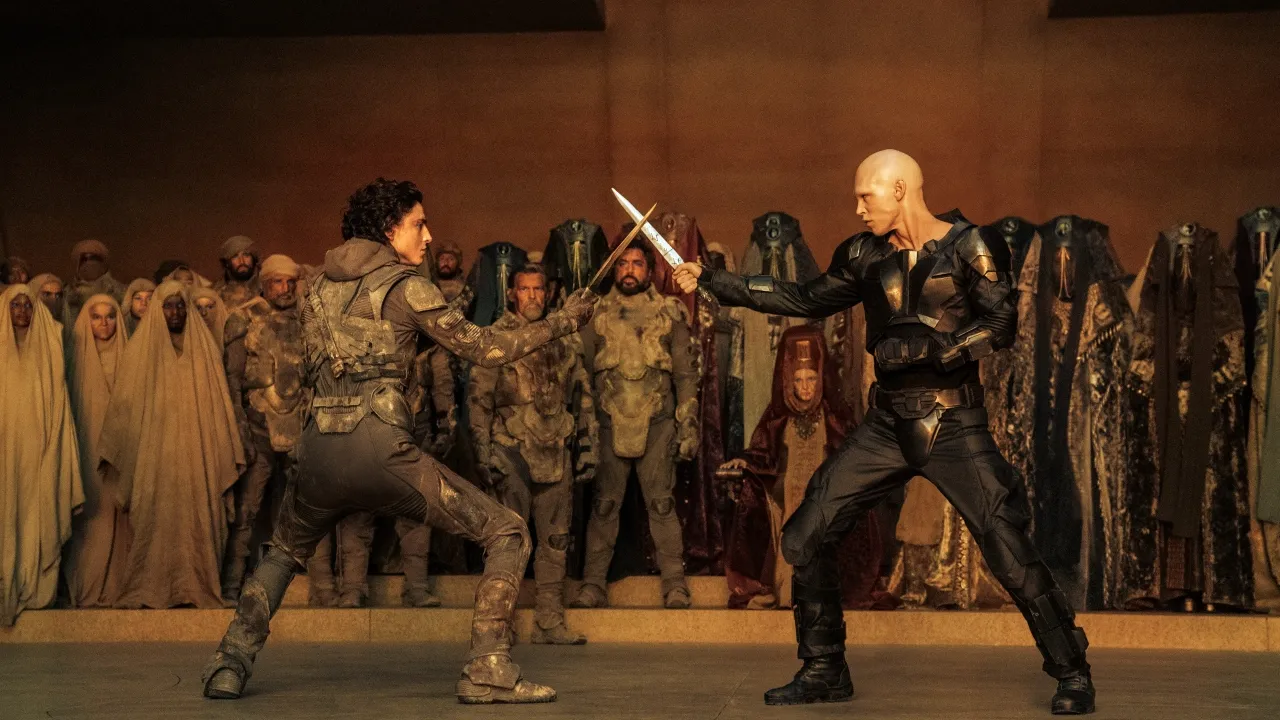

Audiences worldwide flocked to consume the inspiring themes that Dune Part Two portrayed. Image credit: TMDB

Space opera gives you a canvas where fundamental questions about power, survival, and identity can play out without the weight of immediate guilt.

You're not being asked to fix anything. You're being asked to see how systems function, how individuals navigate impossible structures, how cultures clash and adapt across impossible distances.

The space opera subgenre continues to captivate readers because it "combines the wonder of space exploration with deeply resonant character journeys," providing

"a canvas for exploring fundamental questions about humanity's place among the stars."

That's not escapism. That's distance with purpose.

Climate fiction operates in the realm of what you should do. Space opera operates in the realm of what systems do to people, and what people do within systems. The second question is structurally more interesting because it doesn't assume the answer before the story begins.

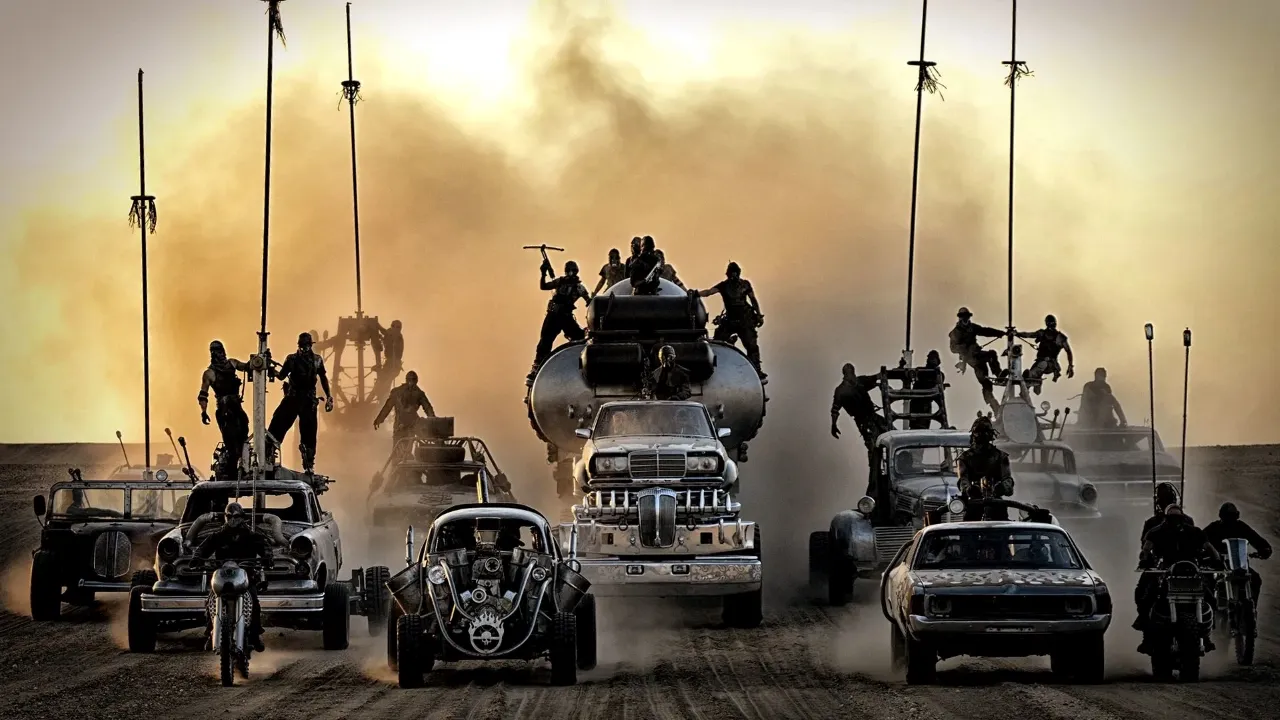

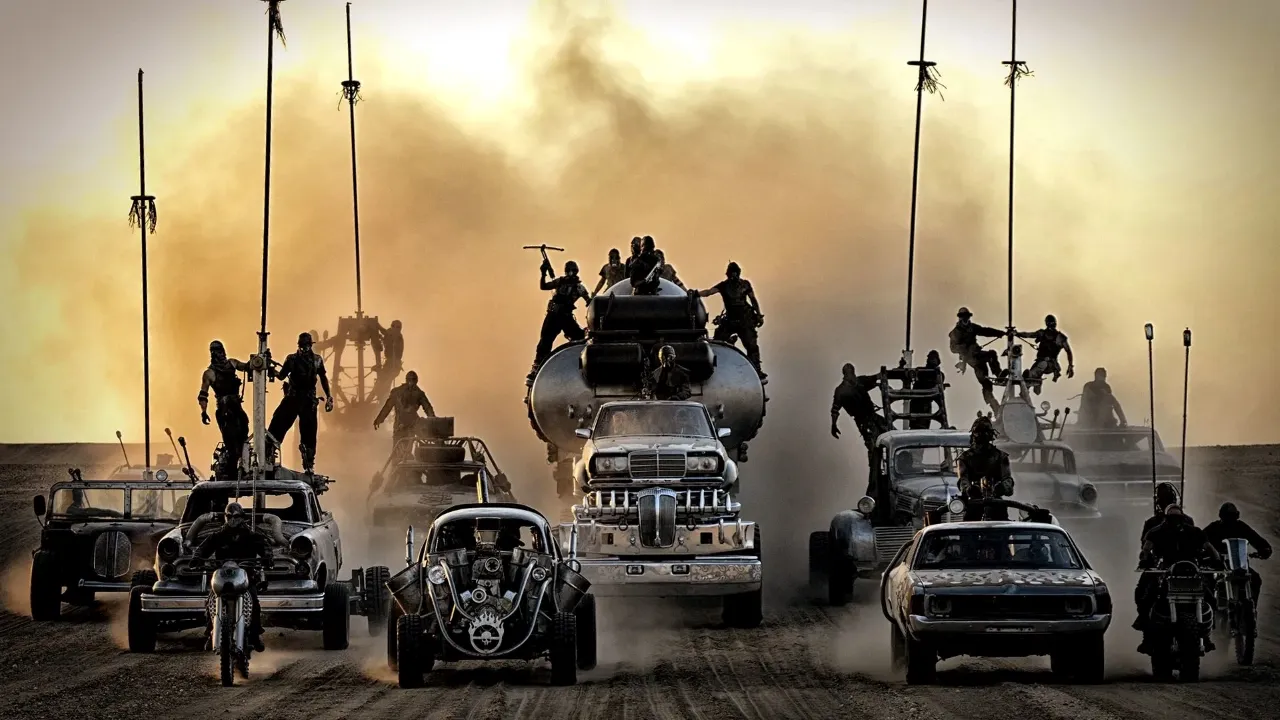

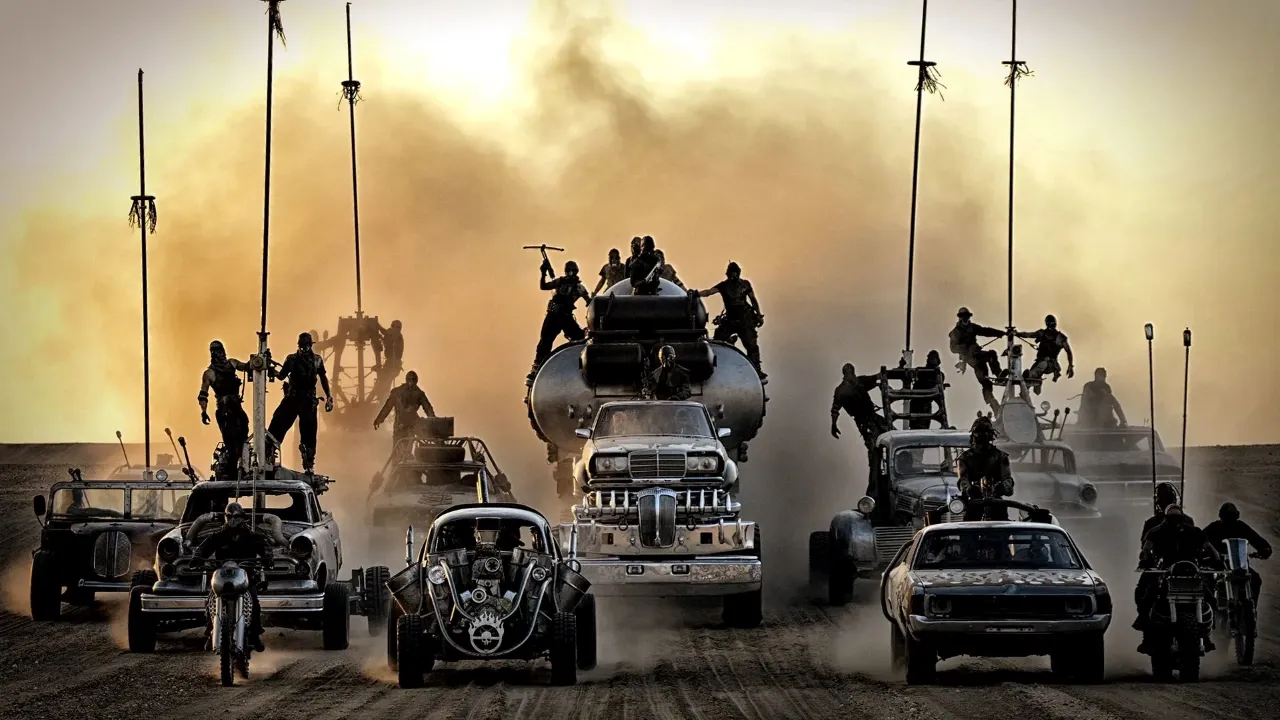

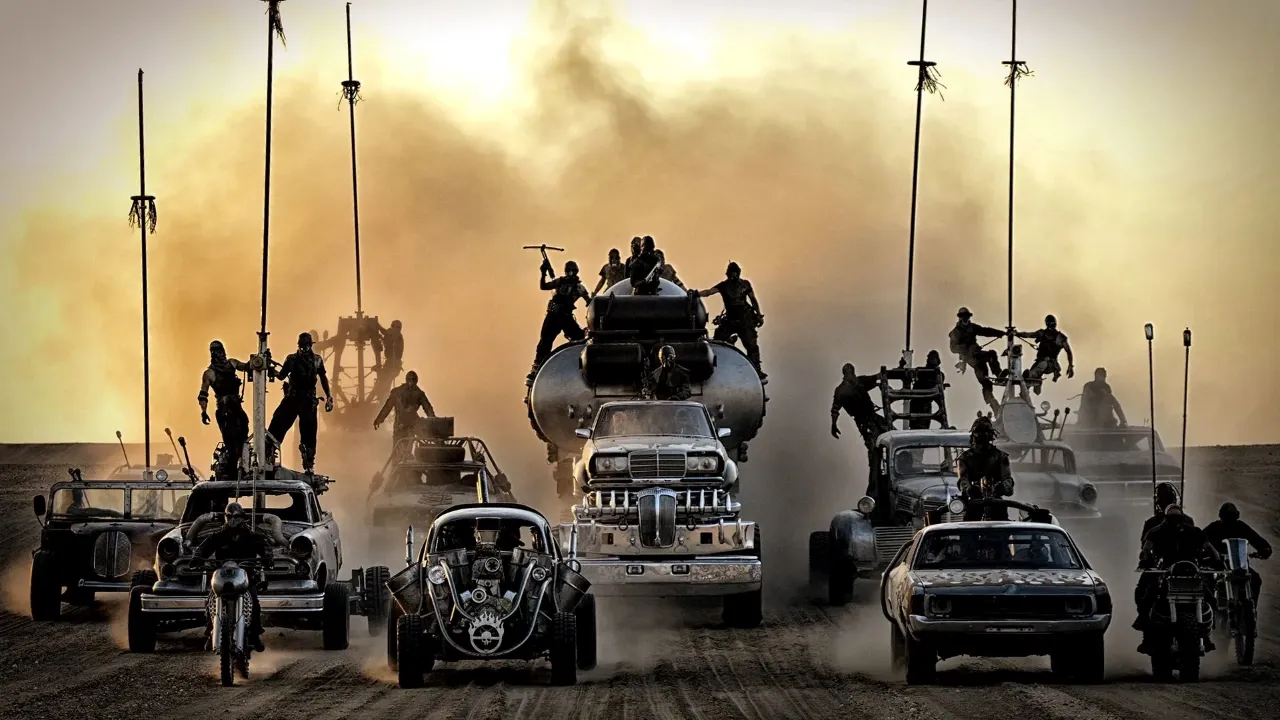

The stunning visuals and poignant themes of Mad Max: Fury Road were not enough to mobilise audiences on en masse. Image credit: TMDB

The Fatigue Problem

Climate fiction is also exhausting its audience.

A 2021 Lancet study found that over 80% of young adults aged 16-25 experience climate anxiety, with 59% reporting they're "extremely worried." More than two-thirds of Americans feel climate anxiety according to Harvard research.

When your audience is already saturated with dread, adding more doesn't create action. It creates shutdown.

Stanford biological anthropologist James Holland Jones argues that climate fiction's dominance of "post-apocalyptic environmental cacotopia" narratives "can sap people's hope about the future, make the effects of environmental change seem fantastical and make people feel like they lack control over the future."

Space opera doesn't pretend the future is solved. It just doesn't start from the assumption that you're already failing.

What This Means for Storytelling

I'm not saying climate fiction doesn't matter. I'm saying it's structurally misaligned with what audiences need from fiction right now.

Space opera succeeds because it treats its audience as capable of understanding complexity without needing to be lectured. It builds worlds that function as living systems with internal logic and consequences. It lets characters complicate those systems rather than merely react to them.

Climate fiction, in its current form, operates as a warning system. Space opera operates as a thinking system.

Denis Villeneuve has been elevated "up there with Christopher Nolan as a filmmaker whose name alone inspires people to go to the movie theatre." That's not about spectacle. It's about trust. Audiences trust him to take them somewhere structurally interesting, not just visually impressive.

The question isn't whether climate fiction can catch up. The question is whether it's willing to stop treating its audience as a problem to be solved and start treating them as participants in a system worth examining.

Right now, space opera is doing that work. Climate fiction is still trying to wake people up who are already awake.

The difference matters more than the genre label suggests.

I've been watching two genres compete for cultural attention, and the winner isn't the one you'd expect.

Climate fiction should be dominating. We're living through the crisis it depicts. The stakes are real, immediate, and measurable. Yet when I look at what's actually moving audiences, what's creating shared cultural moments, what's making people show up—it's space opera.

Dune: Part Two opened to $178.5 million globally in March 2024, nearly doubling its predecessor's debut, and went on to gross a staggering $714.8 million in total. Warner Bros. president Jeff Goldstein called it a moment that "really permeated the culture." That's not franchise momentum. That's something else.

To illustrate this paradox, look no further than Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)—arguably the most celebrated climate fiction film of the last decade. Directed by George Miller, the film is set in a world ravaged by ecological collapse and water scarcity, making it a quintessential example of Hollywood climate fiction. Mad Max: Fury Road grossed $380.4 million worldwide—an impressive figure, but still less than many space opera blockbusters.

The Architecture of Impact

Climate fiction operates under a structural handicap it can't escape.

Research from Duke University Press found that climate fiction provokes environmental anxieties but produces minimal behavioural change. Readers adopt solitary consumption-based measures—recycling more, buying different products—but rarely pursue collective action or systemic engagement.

The genre raises awareness without creating momentum. It makes you feel the problem without showing you the system.

Colby College Professor Matthew Schneider-Mayerson studied climate fiction's effects and concluded:

"We sometimes fetishize raising awareness. Awareness is valuable, but we're aware of lots of things that never affect the way that we act."

Space opera doesn't have this problem because it isn't trying to solve the same equation.

What Space Opera Actually Does

Audiences worldwide flocked to consume the inspiring themes that Dune Part Two portrayed. Image credit: TMDB

Space opera gives you a canvas where fundamental questions about power, survival, and identity can play out without the weight of immediate guilt.

You're not being asked to fix anything. You're being asked to see how systems function, how individuals navigate impossible structures, how cultures clash and adapt across impossible distances.

The space opera subgenre continues to captivate readers because it "combines the wonder of space exploration with deeply resonant character journeys," providing

"a canvas for exploring fundamental questions about humanity's place among the stars."

That's not escapism. That's distance with purpose.

Climate fiction operates in the realm of what you should do. Space opera operates in the realm of what systems do to people, and what people do within systems. The second question is structurally more interesting because it doesn't assume the answer before the story begins.

The stunning visuals and poignant themes of Mad Max: Fury Road were not enough to mobilise audiences on en masse. Image credit: TMDB

The Fatigue Problem

Climate fiction is also exhausting its audience.

A 2021 Lancet study found that over 80% of young adults aged 16-25 experience climate anxiety, with 59% reporting they're "extremely worried." More than two-thirds of Americans feel climate anxiety according to Harvard research.

When your audience is already saturated with dread, adding more doesn't create action. It creates shutdown.

Stanford biological anthropologist James Holland Jones argues that climate fiction's dominance of "post-apocalyptic environmental cacotopia" narratives "can sap people's hope about the future, make the effects of environmental change seem fantastical and make people feel like they lack control over the future."

Space opera doesn't pretend the future is solved. It just doesn't start from the assumption that you're already failing.

What This Means for Storytelling

I'm not saying climate fiction doesn't matter. I'm saying it's structurally misaligned with what audiences need from fiction right now.

Space opera succeeds because it treats its audience as capable of understanding complexity without needing to be lectured. It builds worlds that function as living systems with internal logic and consequences. It lets characters complicate those systems rather than merely react to them.

Climate fiction, in its current form, operates as a warning system. Space opera operates as a thinking system.

Denis Villeneuve has been elevated "up there with Christopher Nolan as a filmmaker whose name alone inspires people to go to the movie theatre." That's not about spectacle. It's about trust. Audiences trust him to take them somewhere structurally interesting, not just visually impressive.

The question isn't whether climate fiction can catch up. The question is whether it's willing to stop treating its audience as a problem to be solved and start treating them as participants in a system worth examining.

Right now, space opera is doing that work. Climate fiction is still trying to wake people up who are already awake.

The difference matters more than the genre label suggests.

Image Gallery

Join the Crew

Related Posts

If you make a purchase through links on this site, we may earn a small commission. This helps keep the blog running and allows us to continue creating cosmic content. Thank you for your support.

Comments

Please be kind and considerate. Any abusive or offensive comments will be sent out the airlock! Thank You.

Please be kind and considerate. Any abusive or offensive comments will be sent out the airlock! Thank You.

Please be kind and considerate. Any abusive or offensive comments will be sent out the airlock! Thank You.

Share on Instagram

Share on Instagram

Banner Image - SciNexic.com

Main Article - All images and media are the property of their respective owners.